History of the Club

During my senior year at Hopkins I decided to try to pull together as much

information about the Club as I could. Along with the invitations to the

1980 Show, I sent a request for stories or memories and was rewarded with a

lot of information. I also interviewed alumni in Baltimore and spent a lot

of time rooting around the closets of the Club house, the medical archives

at Hopkins, and the Welch Medical Library. This history was originally

written in 1980 and then updated in 2003 after I found and bought the 1915

Constitution on ebay. The most recent major revision was in May, 2009 after a presentation to the American Osler Society by Dr. William H. Jarrett, II (class of 1958) entitled "The Pithotomy Club: R.I.P." Dr. Jarrett kindly provided new material, especially audio and photographs to include here. This document will never be complete and I welcome any additions or corrections from readers.

THE PITHOTOMY CLUB

By Robert A. Harrell MD

INTRODUCTION

THE FOUNDING OF THE PITHOTOMY CLUB

Although the exact details of the founding of the Pithotomy Club are probably lost forever, the basic facts can be pieced together. When the Johns Hopkins Medical School opened in 1893 it was a dramatic departure from existing medical education in this country. The entrance requirements of the school were unprecedented (e.g., a bachelor's degree and a "good reading knowledge of French and German"), as was the medical school's graded four-year curriculum. Certainly then, a special sort of person would enroll at this new, untried school. The first class was composed of eighteen students, any one of whom could have entered the older and better known medical schools. By the nature of their pioneering spirit, small number, and their common daily activities, they must have been a close group. The faculty, too, was relatively small in number and was highly committed to the students. It is not surprising, therefore, that the Pithotomy Club, with its goal of promoting the sense of brotherhood between the students themselves and between students and faculty, would develop in this atmosphere. LEFT: An early guest of the Pithotomy Club.

LEFT: An early guest of the Pithotomy Club.

(photograph courtesy of the Pithotomy Club)

The Club was actually formed during the senior year of the first Johns Hopkins Medical School Class, 1896-1897. William G. MacCallum and Joseph L. Nichols had rented a house at 1200 Guilford Avenue and as a housewarming celebration invited Drs. William Welch and William Osler, other faculty members, and friends to the house and entertained them with a keg of beer. These gatherings were repeated several times and finally several classmates joined MacCallum and Nichols to organize a club that could foster the spirit of student-faculty friendship.

Of the eighteen members of the first medical school class at Hopkins, nine were founding members of the Pithotomy Club: Charles Bardeen from Harvard, Thomas R. Brown from Johns Hopkins, Lester W. Day from Yale, Louis P. Hamburger from Johns Hopkins, William George MacCallum who transferred from the Toronto University School of Medicine, James F. Mitchell from Johns Hopkins, Joseph Nichols from Harvard, Eugene L. Opie who transferred from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Baltimore, and Richard P. Strong from Yale.

LEFT: Founding members of the Pithotomy Club.

The name "Pithotomy" was devised by MacCallum who, according to legend, combined the Greek words pithos, meaning vessel, and otomos, meaning to open. Together the words mean, to Pithotomists at least, "to tap a keg." In the early days the Club served chiefly as a means for facilitating informal student-faculty contact. Membership was restricted to the top members of the senior class, so in that sense the Club was an honorary society. A Constitution was written by hand, including the title page, "Constitution of the Pithotomists, Johns Hopkins Medical School, Baltimore, Maryland, 1897." The constitution begins with:

Article I: NameThe constitution continues on in this manner and was amended over the years.

Section 1. The name of the society shall be "The Society of Pithotomists."

Article II: Object

Section 1. The object of this society is the promotion of vice among the virtuous,

virtue among the vicious, and good fellowship among all.

In addition, the purpose of the Club was to "facilitate the advancement of its members in the art and science of medicine by the promotion of social intercourse between the faculty and students of the Society."

In 1897, Max Broedel, later the first Chairman of Art as Applied to Medicine, prepared for the Club his well known drawing of the cherub on a bee r keg which has become the symbol of the club as well as the inspiration for the manner in which the song "3000 Years Ago" has been performed. Dr. Robert Mason ('42) talked about the drawing with Max Broedel late in the artist's life and was provided the following explanation. The drawing is set in Kottler's Restaurant in Berlin. The figure on the keg is Gambrinus, the legendary "King of Beer." The cap represents scholarship while under the keg is a liquid effluent collector of the type used in the delivery suite and the instrument tables are also from the delivery suite. The owl, beer mug, staff, and discarded fourth-year examination need no explanation. The dog and the cat are William Welch's. The sausages represent entrails from a patient.

THE TURN OF THE CENTURY

The decade of the turn of the century saw the advent of the Pithotomy Show, the annual event for which the Club is best known, and one of the major events of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. By participating in the show, students vented four years of frustration toward the faculty while retaining their affection for individual faculty members. For the faculty, the show provided more than a chance to "see ourselves as others see us" by allowing them to spend an informal evening with their colleagues, drink a little too much, sing a little too loudly, and relive what for some professors was decades of show attendance. Although Harvey Cushing in his biography of William Osler mentions Pithotomy gatherings as early as 1897 in which "the foibles of the teachers in particular were not spared in burlesque," the modern show probably began in either 1905 or 1906. In its earliest years it was tamer than the more recent bawdy performances. Dr. Ernest Cross, Jr. ('41) provided the information that his father, a member of the class of 1906, played the part of Dr. Henry Hurd, superintendent of the Johns Hopkins Hospital, in one of the first shows. Apparently Dr. Hurd had a small dog and was portrayed in the show pulling a toy dog on wheels.From its inception faculty members were frequent guests of the Pithotomy Club. Letters from Welch, Osler, and others accepting invitations to the Club are still in existence in the archives of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. For some years the Club functioned as an honorary society for the senior students, as only the top members of each senior class were selected for membership. In its early years the Johns Hopkins Hospital reportedly chose its interns based purely on class rank, the top six members being offered internships in medicine and the next six offered positions in surgery. Since those students were usually in the Pithotomy Club, many positions were traded at the Club itself.

One well known member of the Club at this time was George Hoyt Whipple of the class of 1905 who was awarded the Nobel Prize in medicine in 1934. Poker was a favorite activity of the Pithotomists and Whipple with his "poker face" was said to have been one of the best at this amusement. During this period, the Club was overseen by the alumni, particularly the founding members, who made sure that the Club did not deviate too far from their original intentions.

The Club was not always popular with its neighbors, perhaps because being in a rowhouse made the Club a bit too close to its neighbors. One neighbor wrote a letter to Dr. Hurd dated April 26, 1907 saying:

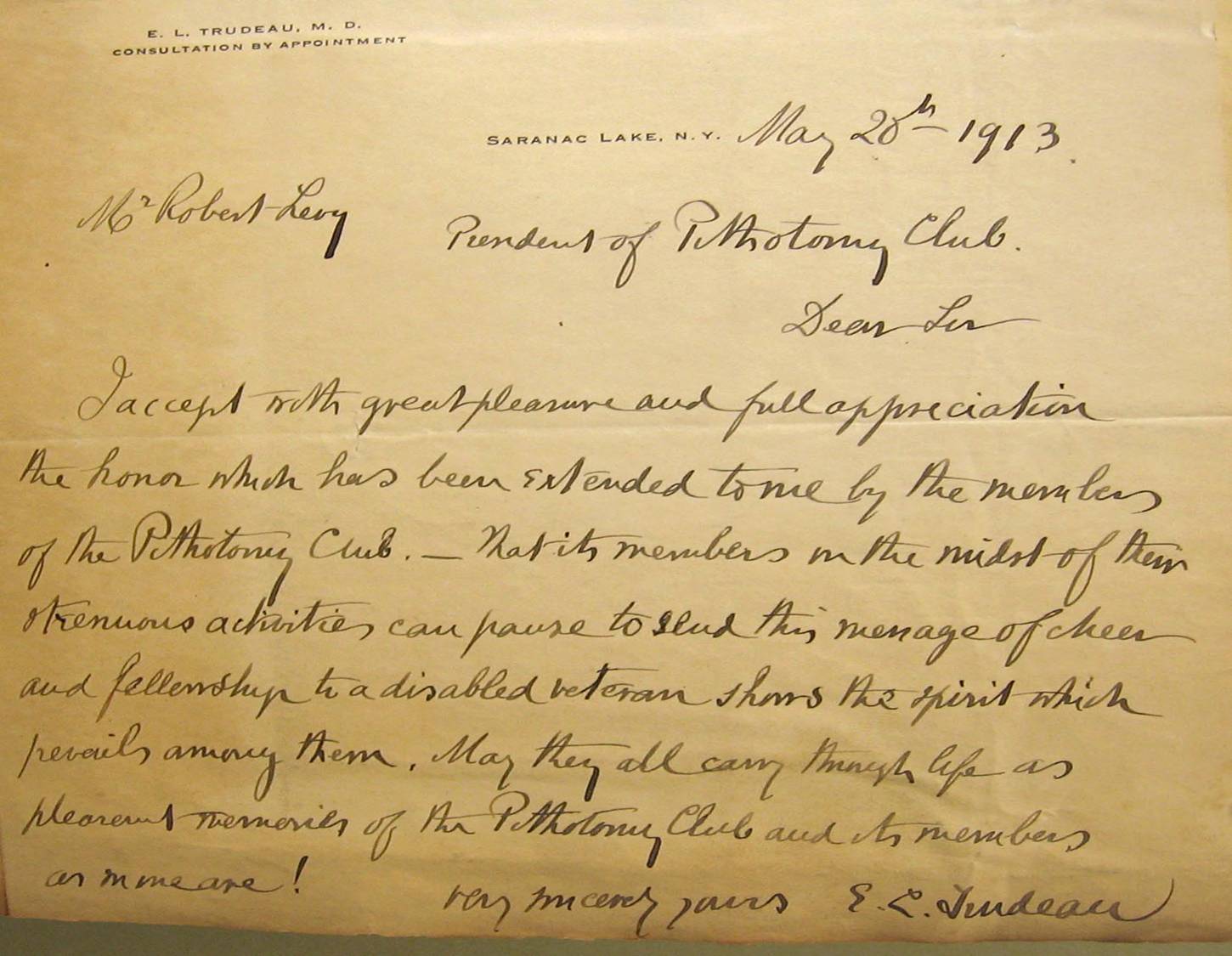

I am sorry to have to complain but the behavior of the Doctor Club at 510 N. Broadway is scandalous - their beer parties lasting all night up until 2 o'clock in the morning - keeping us up not getting any sleep with their screaming and running and playing the piano. Mr. ________ and myself have spoken to them but it does not appear to have any effect so I thought I would write and let the professors know of it.Another letter complained of "card games and beer in the rooms" and of Club members "jumping down stairs instead of walking down." Of the many visitors to the Johns Hopkins Hospital in the course of a year, some were invited to the Pithotomy Club. One of these was Dr. Edward L. Trudeau, best known for founding the tuberculosis sanatorium and research laboratory at Saranac Lake, New York. Trudeau so enjoyed a visit in 1912 that he wrote the following letter.

The men at the Pithotomy Club have a new fireplace and I have such pleasant recollections of an evening when I met the members in that room and enjoyed their hospitality that I would be very glad to donate the fireplace and have in a way a permanent place at the club's hospitable fireside. Would such a gift be acceptable? If so, it would give me a great deal of pleasure to give it if you could order the work done and send me the bill. Perhaps some day yet I may sit there again with the members.Such a gift apparently was acceptable because the work was done and Trudeau wrote another letter several months later, enclosing a check.

I am sending a check to your order for the bill for the fireplace at the Club. It is a great pleasure to me to feel that I am represented there in some way and I am hoping I may yet someday sit down with the members and warm my toes by the fireplace and my battered old cardiac apparatus by the cheer of the young doctors who are just starting out on the road I have traveled long. My best wishes to the Pithotomy Club members.The wooden fireplace mantle, with its familiar engraving, "In memory of a pleasant evening spent with the boys, E.L.T., 1912," was for many years located in the dining room of the Club.

THE POST WWI PERIOD AND THE 1920's

The era immediately after World War I was a unique one at Johns Hopkins and Pithotomy. Although many of the entering freshmen had served in the military and hence were older than many of the upperclassmen, they looked up to the upperclassmen with respectful admiration. Furthermore, Pithotomy alumni had by this time begun to assume an active role in supporting the Club and maintaining its traditions, Louis Hamburger ('97), Tom Brown ('97), W.G. MacCallum ('97), and Dick Follis ('99) being the most active alumni. Many spring evenings were spent by Pithotomy members sitting on the white marble steps of the Club talking or playing games. One game involved counting passersby going in each direction, with bets made as to the number who would pass each way.

LEFT: 510 N. Broadway

Prohibition complicated acquiring alcoholic beverages for parties and for general enjoyment. Buying "needle beer" from a bar on Wolfe Street was never a problem, but more potent forms of alcohol were more of a challenge to find, though farmers would sometimes deliver whiskey to the Club in milk cans. On one occasion a sailor was paid $50 for what was supposed to be good Scotch whiskey which turned out to be a questionable mixture of water, caramel, and pepper. Two students who worked in a laboratory over the summer of 1922-23 were able to smuggle out 95% alcohol. They stored this contraband at the Club but hid it because the fall cleaning would take place while they were home on vacation. Before the Fall Dance that year these two students mysteriously came upon a "treasure map" which purported to lead to a cache of alcohol. The map met with much skeptical laughter from the other Pithotomists, who were then astonished when the map led to ten bottles of potent alcohol.

By this time the Pithotomy Show had become a solid tradition. One unwritten rule was broken in the 1920's, however. Because women were not allowed to attend the show, they were never mentioned in it. On one occasion a questionable comment was made about Hugh Young's secretary. Dr. Young, Chairman of the Urology Department, apparently became upset by this and, according to rumor, told the club president, who was hoping to become a ur ologist, to find another specialty.

One event of the mid-20's stands out in Pithotomy Club history. At that time the Club was cared for by a married couple, the wife being the cook and the husband the butler. For reasons unknown, during the Christmas vacation of 1924 the butler fatally shot his wife. Because he was so popular with the Pithotomists, they retained a prominent Baltimore attorney, a Mr. Marburg, to defend him. In spite of careful coaching, when asked at his trial if he had murdered in a fit of anger the butler replied, "No, I intended to kill her on Wednesday but didn't get a chance so had to do it on Thursday." He went to prison for life, where he was periodically visited by Pithotomists. At one point a group of Pithotomists performed a lumbar puncture on him in jail, using ether to calm him. He was thought to have syphilis and cirrhosis.

The Pithotomy Club dances of the 1920's were considered a great social event in Baltimore. The dances took place in the fall of each year. Club members usually had to borrow clothes for the event. Debutantes from the outlying parts of the city were invited, and many Pithotomists met their future wives at these dances. There was a band, and if the weather allowed, dancing even took place on Broadway in front of the Club.

During the 1920's invitations to join Pithotomy often depended upon knowing the right people, such as through an Ivy League college or natives of Baltimore. In any case, the invitations were offered in an informal manner.

An outbreak of rats in the clubhouse was a major problem during the 1920's, a situation that worsened after the Baltimore docks burned. Rats overran the food-storage area in the basement of the building and could be heard gnawing holes in the door next to the tin that had been nailed over the most recently made hole. Members found various techniques for dealing with the rats. C. C. Nuckols, Jr. ('33) writes of being surprised one night by a large rat stretched across two shelves in a storage area. He instinctively threw the mug of milk he was carrying at the beast, striking it in the back and killing it. Another enterprising Pithotomist frequently waited quietly on the cushion of the window seat in order to shoot the rats with a .22 rifle as they came across the floor, using only the streetlights to see. Julian Chisholm ('30) would sneak into the food storeroom at night armed only with a stick and coat hanger. Turning on the lights, he thrashed the weapons about and with a great deal of noise could kill some of the brutes while miraculously avoiding being bitten.

At this time a favorite hangout was a speakeasy about three blocks from the Club, run by a man named Jim. Because he had married the daughter of a police captain he had access to good beer. In addition, oysters, crabs, and shrimp were served at a reasonable price. If the hospital telephone operator could not locate an intern, she would try Jim's and he could usually be found there. Activities at the Club at this time included blackjack and poker. However, bridge was the overriding passion of many members. Since the class of 1932 had only four members, it was often said, presumably in jest, that invitations to join were held to this number so that the game could be played without interruptions from other classmates. Tiddlywinks was also quite popular with countless tournaments being held on a blanket-covered table. The Club had a piano and singing was an enjoyable after dinner activity.

As always, during the late 1920's the Pithotomy Show completed the year. Preparations included bracing the first floor of the Club with heavy timbers to accommodate the expected mob. The ageless profanity of the show became evident in this era. At the end of each Pithotomy Show, "3000 Years Ago" was sung by a senior appropriately attired in a mortarboard, sitting on a keg, simulating the Max Broedel drawing. He would be accompanied on stage by three other members portraying Osler, Halsted, and Kelly (please go to the "3000 Years Ago" section for further details). The music for the song is credited to Ralph Bowers ('25), though the lyrics are not appropriate for publication.

The beer slide was also a popular activity after the show. If enough beer was not already present, which is difficult to imagine, additional beer was poured on the floor so that the floor was quite slick. Members of the house staff were then chosen, either because of seniority or lack of popularity, and sent sliding across the floor. A. McGehee Harvey tells of smashing a beer mug into his face while being slid, resulting in a prominent black eye. He found it necessary to wear sunglasses the next day while entertaining a visiting professor. The uniforms worn during the revelry were deposited in the hallways of what is now the Billings Building, the famous domed building, where the residents lived at that time. They created an awful stench of stale beer by the next morning.

Another part of the show was the limerick chorus in which over a dozen men ranging from students to professors would form a circle with arms intertwined. They would shout out limericks, with a pause during which a chant of "Won't you come up to me?" was voiced. Members of the circle who had a limerick would then be called upon to say it. These sessions went on for considerable lengths of time without repetition. The final activity of the evening of the show was gambling with games sometimes lasting into the next day.

From World War I to World War II the Club was managed by Dr. Richard Follis, who saw to it that the Club never got itself into too much financial or legal trouble. But, as always, the Pithotomists were quite independent in their attitudes and actions.

THE 1930's

The decade of the 1930's at the Pithotomy Club was similar to that of the '20's except that the students had even less money. "Jim's" on Orleans Street continued to be a popular gathering place for students, interns, and residents.Invitations to join the Club were still informal and generally went to graduates of Ivy League colleges. Graduates of the Johns Hopkins University Homewood Campus were not generally considered for membership. Social activities included "fire drills" or parties on Saturday nights. Bridge games after lunch were popular and poker playing was common. The shows were enthusiastically supported by the faculty and most attended them. Dr. Warfield Firor was considered the best professor and a good friend by the students. Dr. Edwards Park, Professor of Pediatrics, was considered so "sweet" that he was not treated roughly in the shows.

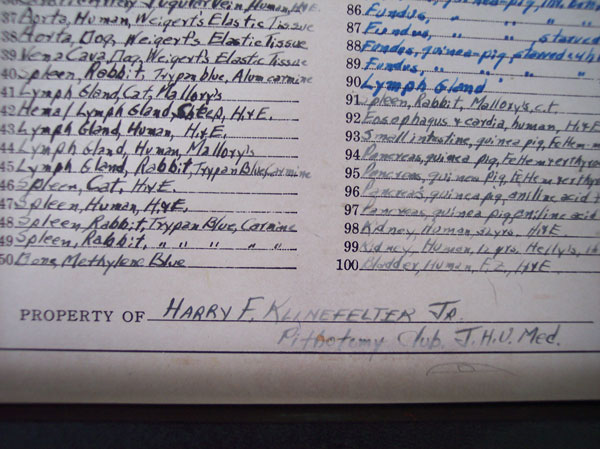

LEFT: Medical school slide set belonging to Harry Klinefelter, Class of 1937.

LEFT: Medical school slide set belonging to Harry Klinefelter, Class of 1937.

The Pithotomy Show was described with great accuracy by F. Scott Fitzgerald in his short story, "One Interne," first published in 1932. Fitzgerald writes, "Two hundred doctors and students sweltered in the reception rooms of the old narrow house and another two hundred students pressed in at the doors, effectually sealing out any breezes from the Maryland night." The story includes a verse of "3000 Years Ago" which he describes as a "witty, scurrilous and interminable song which described the failings and eccentricities of the medical faculty." He also describes preparation for the beer slide. "After the show the older men departed, the floors were sloshed with beer and the traditional roughhouse usurped the evening."

One Pithotomy Show prank that occurred at this time has become legendary. Duke University was beginning its medical school and was searching for a chairman for the Department of Surgery. Two Johns Hopkins surgeons were being considered for the job, William F. Rienhoff, Jr., who was chief resident from 1923-25, and J. Deryl Hart who was chief resident from 1927-29. Duke sent a committee to Baltimore to interview "Wild Bill" Rienhoff. Being a loyal Pithotomist, he had just donated a portrait of himself to the Club, and since it was time for the Pithotomy Show he invited members of the Duke commi ttee to accompany him to the show. They accepted the invitation and joined Dr. Rienhoff on the front row. During the show it was announced that a portrait of Dr. Rienhoff would be unveiled that evening. With all proper pomp, a portrait was brought to the stage. When unveiled, however, it proved to be a realistic portrait of a horse's rear. Dr. Rienhoff was very much insulted and resigned from the Club the next morning and did not set foot in the Club again for over five years. For historical completeness it might be added that Dr. Hart accepted the position at Duke and later became the president of Duke University. Eventually, Dr. Rienhoff overcame his anger and became one of the club's strongest supporters. On many occasions he provided money when the Club was in financial need. Shortly after WWII he donated a very expensive pool table to the Club, and later a television set. He continued to be a favorite target of abuse at the Pithotomy Show, but enjoyed it, being highly upset if his name failed to appear on the program. During the late 1930's the year began with rush week for the Pithotomy Club and the Hopkins chapter of four medical student fraternities. Invitations to join the Club would be offered to those who impressed the members. Pithotomy Club membership was considered desirable because of the large number of faculty sons, sons of physicians, and Baltimore natives in the Club. The selection process was not perfect however. One incoming student presented impressive credentials and was quickly accepted. He was said to have been a relative of the obstetrician of the royal family of Japan, a member of the Japanese Davis Cup team, and to have had experience in experimental surgery. When it was discovered that these qualifications were fraudulent he left Hopkins. Apparently he was actually a houseboy who had been sent to medical school by his employer because he was so eager to become a physician. Initiation of new members was a simple affair. A special lunch was held and new members stood in succession and were given a slip of paper with a subject written on it. The neophyte was then expected to give an impromptu talk on the assigned subject, which was always obscene.

At that time an elderly woman named Burr supervised the preparation of the food, which was very good. The Pithotomy Club served an important function because there were no dormitories and many students lived in boarding houses where good food was often not available. Tuberculosis was a risk for the malnourished students, being prevalent in Baltimore, so it was beneficial for them to be able to get nutritious meals. Poker had become the most popular after dinner activity and was played for ten cents a chip.

Social life around the Johns Hopkins Hospital centered on Broadway. Jim's had acquired the new name, "New Broadway Hotel," and continued to be popular. On Saturday nights the Pithotomy Club and the medical student fraternities, also located on Broadway, sponsored dances in succession to which everyone was invited. A small orchestra usually played and there were many young women from Baltimore to liven up the evening.

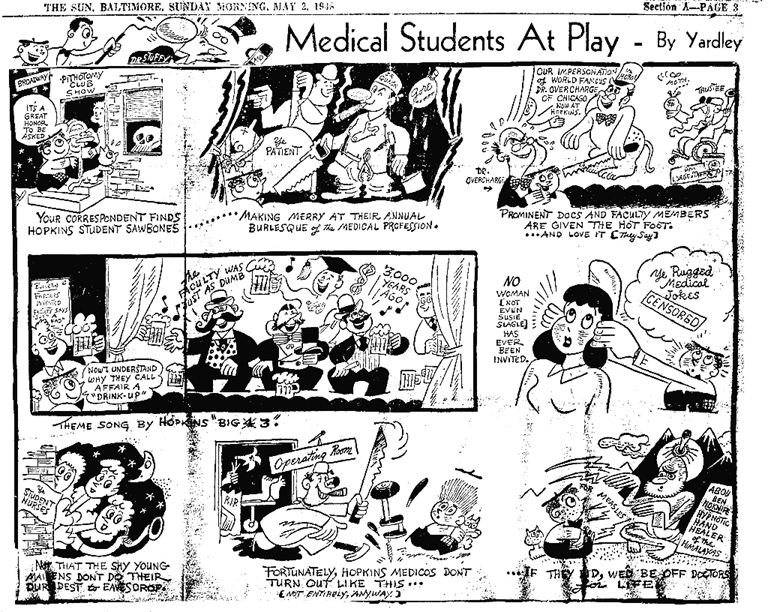

The Pithotomy Show continued to be the highlight of the year. On Friday night the house staff and students attended and the beer slide remained a popular post-show activity. Saturday night's show had a far more distinguished audience with most department chairs attending regularly. The front row was occupied by Max Broedel, Thomas Cullen, H.L. Mencken, and often by Yardley, the Baltimore Sun cartoonist. Reportedly, the mayor of Baltimore or the governor of Maryland would attend on occasion. After the show, the audience would gather around the piano for endless singing of "3000 Years Ago." The faculty often got up on stage after the show to join in the singing and dancing. Gambling continued to be a popular after-show activity.

One show scene presented around 1940 lampooned the early research in artificial insemination being carried out at that time in Hopkins. All sorts of bizarre noises were heard off stage, which were said to represent the acquisition of a specimen. The researcher then walked on stage carrying a bowl containing goldfish and dry ice, exclaiming, "Look at the little bastards swim."

At this time the Department of Surgery was in a state of transition because Dean Lewis was retiring as chairman and his successor was being sought. This situation was commemorated in a show scene which took place in a bathroom in which all the department chairmen were sitting on toilets discussing the selection of the new Chairman of Surgery. Each chairman rose and sang a song about himself. Warfield Longcope, Professor of Medicine, was portrayed singing the following song:

I'm chieftan of the dosing men of this great teaching staff.Department L was the VD clinic at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

If I ever got a dose myself Department L would laugh.

I demand that all nephritics have a sheaf of useless charts,

There's a page for every turd they make and the odor of their farts.

We're the committee to pick a surgeon man.

He must have brass and kiss their ass to occupy this can.

By that time Dr. Longcope was quite hard of hearing and came to the show with Dr. Alan Chesney, Dean of the Medical Faculty, who was also hard of hearing. They consequently asked a younger man to accompany them to tell them what was being said. At one point something was said onstage about Longcope. When Longcope asked the younger man what had been said, he hesitated to answer but finally told Longcope, "They called you an old son of a bitch." Longcope roared with laughter and replied, "That's great. That's very accurate."

THE 1940's

Despite World War II, the Pithotomy Club continued to thrive as usual during the early 1940's. The painting based on the Max Broedel drawing which hung over the mantelpiece of the club was painted in 1942. Ben Baker's aunt painted it, and it is actually the second one she did, the first one belonging to Mason Andrews of Norfolk, Virginia.The earliest Pithotomy Show program known to be in existence is from 1942, the 77th Pithotomy Show. Because the early gatherings of students and faculty were called "Pithotomies," the numbering system of shows is built on top of these early gatherings. Consequently, number of each show exceeds the number of shows actually performed. During this time the program was printed on one side of a sheet of paper but the style was quite similar to that used for years to come. The fake advertisements were there, for example, "Charcot's Joint" advertised music by Lues Gumma and his Condylomata Orchestra with "tabies for ladies" and a "most congenital crowd." Faculty names were already being altered for the program; for example "Farafield Furor" for the acting Surgeon-in-Chief, "Buni Faker" for a Pithotomist on the medical faculty, and an "All-in-Jazzme" for the Dean of the Medical Faculty and past president of the Pithotomy Club.

Outside guests continued to frequent the show. One of these was the Commissioner of Police who, possibly because he was a graduate of Princeton, enjoyed the shows. One year the neighbors complained about the noise and a police sergeant came to investigate. He began yelling at the Pithotomists, then looked up, saw his boss, stopped in mid-sentence, and saluted. In spite of a sign saying "Games of Chance Upstairs," which was on the wall directly above the Commissioner's head, the matter was not pursued further. Another legal problem of this era was the program for the show. At that time printers refused to print the unseemly words that appeared in the program, but fortunately the family of a Pithotomist owned a printing company which printed the programs for the Club.

The beautiful mahogany paneling decor ating the Clubhouse was acquired by members of the class of 1943. They installed all of the paneling themselves and ran into some slight difficulty when one member was hammering a bit too hard and knocked a brick into the bed of the neighbor from the adjoining rowhouse who was apparently entertaining a young woman at the time. Because of the war, food was difficult to get and meals were not very good. Many meals consisted of scrambled eggs. In spite of this, Dr. Arnold Rich, Professor of Pathology, would often come to the Club for meals.

The Club was still located at 510 N. Broadway. Upon entering the Clubhouse, one first came into the living room which was paneled, had sofas and chairs, a nice fireplace, and the piano. The long, narrow kitchen contained about six long tables with eight to ten chairs each. Meals were served three times daily, except for Sunday supper. The pool table was located in the game room on the second floor and was in constant use. Two members lived on the third floor and three on the second floor. Studying stopped at about 11 p.m. for a nightcap at the New Broadway.

LEFT: Pithotomy Wednesday neckwear.

LEFT: Pithotomy Wednesday neckwear.

At this time the "Little Inn" was located two doors away from the Clubhouse and was operated by two delightful spinsters. It housed many VIP's visiting Hopkins and was noted for its fine service. Pithotomists would lodge their weekend dates at the Little Inn when a room was available, but needed references to do so. The New Broadway continued to prosper also. Large pitchers of beer were sold there for 25 cents and if one got a plate of Maryland crabs the beer was free. There was usually a live show on weekends.

The head maid at the Pithotomy Club at this time was named Dorothy and she was overseen by the dietician, Irene, who was the wife of a surgery resident. When Dorothy developed conjunctivitis and was urged to go to the hospital for treatment, she replied, "I would, but every time I go over there they find everything else wrong with me and never help me for what it is I came in for." On another occasion she was asked about the hospital in the old days and said, "My mother would never allow any of us children ever to walk on Monument Street next to that hospital. Haven't you ever heard how a big long arm will reach out of one of the doorways right there next to the sidewalk and pull Black folks inside and they are never seen again. No, I won't walk up that street, never!"

At that time the Pithotomists and other medical students got along well with the inhabitants of East Baltimore. However, the "long arm snatching Black folks" was feared and no one ever slept on the grass median in front of the hospital. Although violence occurred in the neighborhood, anyone working at the hospital was considered a privileged individual and wearing a white uniform afforded immunity from the violence of the area.

The supervision of the Club was taken over by Dr. Ed Broyles from Dr. Follis. He is given credit for creating the Pithotomy tie. Apparently his sister-in-law suggested that such a tie should represent the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, so the Hopkins colors of blue and black, and green symbolizing medicine were chosen. Dr. Broyles and his wife traveled to England on a vacation and he collected different patterns of English cloth. When he finally found the proper pattern, he contacted Brooks Brothers and the first Pithotomy ties were produced. The tie became a central feature of the Pithotomy sense of brotherhood with its familiar blue, black, and green stripes being worn by Pithotomists every Wednesday to this day. [An alternate explanation for the green stripe and green color of the Pithotomy Clubhouse is that the early club dined in a brothel which was painted green and the tradition stuck with the club. This Pithotomy legend is difficult to confirm.]

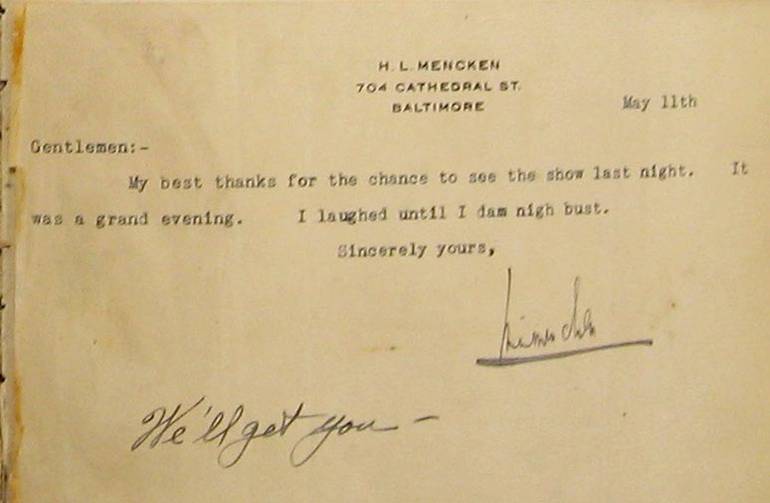

As has been mentioned previously, H. L. Mencken was a Pithotomy Show regular for many years. In 1947, seniors Charles Ellicott and Strother Marshall went to visit Mr. Mencken, hoping to get ideas for that year's show. They were instructed to meet him at 9:15 in the morning in the lobby of the downtown Sunpaper's Building. The lobby was quite ornate, built like a large banking floor with the ceiling two and one half flights up and a balcony around the walls at the second floor level. Mencken, unmistakable with a bowler and cigar even at that hour, strode in on time and with a grunt signified that he was to be followed into the old wrought iron elevator cage. Just below the balcony the elevator operator stopped the cage and it stood there for about five minutes. Mencken seemed unconcerned and merely gazed off into the air to the right and left. Then they ascended to his office. After the meeting the Pithotomists came down in the elevator again and asked the operator if he had gotten the machine fixed. He replied that it had never been broken and then explained, "Mr. Mencken just has me stop there each morning for him to look up under the skirts of the girls coming to work as they walk around the balcony."

RIGHT: 1948 Pithotomy Show. H.L. Mencken is on the right, facing the camera, sitting next to Dr. Arnold Rich and Dr. Bill Rienhoff, Jr, who are enjoying the traditional Pithotomy mint julep.

(Courtesy Dr. Richard Peeler, '51)

The Club received some rare publicity about the show in a 1948 article in the Baltimore Sun. The article included such statements as:

Sitting in one of the rows of chairs which replace the usual clubroom furniture, you would have seen what makes the Pithotomy a name to be reckoned with in the Hopkins. And seated in the first row are some of the greatest names in contemporary medicine. There are no women. It is considered a sign that a man has made his mark at the Hopkins when he is subjected to the withering scorn of the Pithotomists.This same article gives an account of "3000 Years Ago" as performed at that time. Three of the Hopkins Big Four were portrayed but their identities kept secret. In addition, the "cherub," attired almost solely in a scholar's mortar board, sat on a keg smoking a cigar with one hand and holding a mug of beer in the other. This article was accompanied by the well known Yardley cartoon "Medical Students At Play" which depicted the show (below).

THE 1950's

The 90th Pithotomy Show was held in 1951. Of course the faculty names were altered, the chief of medicine being known as "A. McPeePee Hardly." Pithotomists had an important role in the 1952 Christmas party at the "Henhouse," the club for women medical students. The sophomore Pithotomy class was responsible for preparing the "Purple Jesus" and "Sea Breeze" for this event, and obtained large crocks in which to formulate these concoctions. Reputedly, a large fellow in the Club used a correspondingly small fellow as his stirrer in the crock.

1954 was an important year in Pithotomy Club history, being the year of the move from 510 N. Broadway to the club's next location at 731 N. Broadway. In the spring of 1954, as the rowhouses on Broadway were being leveled for new construction, special permission was granted to leave the Pithotomy Club intact until the end of the school year. Thus the Club was the only structure left standing on the entire block. As the last week of school commenced, a large crane bearing a heavy steel ball suspended on a cable was poised ready to deliver the final blow to the building. The night before the building was to be razed an "end of the world" party was held and the Pithotomists virtually dismantled the building without the help of the city. The wood paneling was rescued and moved to the new Clubhouse. Many of the old stone blocks from the front wall of the building were taken by various alumni as souvenirs/

The new Clubhouse was considerably smaller than the original building and was purchased with funds obtained from the sale of the other house. A mortgage to pay for rebuilding the inside of the structure was obtained, and room was made for the pool table and other necessities. The front of the building was painted green in response to strong suggestions and contributions from Dr. Alan Woods, Jr., and his colleagues. They hoped to match the color of the original club, but the new Club ended up being the wrong shade of green. When the front of the Club later cracked, necessitating extensive repairs and new paint, it was hoped to match the Pithotomy tie. Again they were unsuccessful and the Club remained a distasteful, but perhaps charming, color of green. It was in 1954, too, that Dr. Alan Woods, Jr., took over management of the Club from Dr. Ed Broyles. Dr. Woods carefully collected alumni contributions and saw to it that the club remained a viable organization.

The 94th Pithotomy Show was held in 1955. In the program was a review of sorts of a book written by a man who was later to become Physician-in-Chief of the Johns Hopkins Hospital and an honorary Pithotomist. The book, called "Fart Sounds" was by "Victor McFlatus." According to the review the book is a "timely, tympanous treatise on the differential diagnosis of the fizz, fuzz, fizzy-fuzz, tearass and rattler, together with spectro-phono-flatograms and sphincter tensograms associated with the production of each - a must for the assthetically minded."

The Pithotomy Club Flag dates from 1956. In June of that year, a group of seven members went to Europe following completion of their second year of medical school. After a brief period of "work" at Edinburgh's Royal Infirmary and Guy's hospital in London, they went to the Continent. Inspired by the "colorful craft of picturesque Lake Geneva," they decided to have a flag made. A flag maker was contacted and a flag was made composed of stripes the same colors as the Pithotomy tie with the letters "PC" embroidered on it in gold. The flag was presented to the Club in September, 1956, and was thereafter flown at the Clubhouse on special occasions and during the week of the show. It might be added that in 1979 a group of Pithotomists went on a sailing trip in the Bahamas and flew the flag proudly from the mast of their craft, no doubt terrifying other boats in the area.

The Pithotomy Show program in 1956 was the first to have a four-page format. In that show one of the members, who later became a prominent Johns Hopkins faculty member and then department chairman at another medical school, played the part of a six-foot tall penis. After the show several club members, who had sampled a bit too much beer, decided to play a practical joke on him. He was bound and gagged and put into his penis costume. They drove him to Goucher College, where he had a girlfriend, deposited him in front of her dormitory, rang the doorbell and left. Apparently someone at Goucher did not have a Pithotomy sense of humor and called the police. Bail was posted by Dr. Woods and the unfortunate individual did not have to spend the night in jail.

Over the years numerous visitors to Hopkins have had the opportunity of seeing a Pithotomy Show. One of the more prominent was Professor Phillip Allison, who was the Nuffield Professor of Surgery at Oxford and a guest of Dr. Blalock. He was sent an invitation to the 1956 show and responded in a formal manner on stationary that indicated that he was a member of the Queen's Privy Council. In spite of his staid, sophisticated, conservative manner, the members of the Club thought that he should be treated as any other faculty member. Since he was a member of the Privy Council the thought occurred that a commode would be an appropriate seat for him on the front row, which was reserved for senior professors. Consequently, a commode was located in an alley, scrubbed clean, and placed next to the chair reserved for Dr. Blalock. When Dr. Allison arrived, the Pithotomists were quite apprehensive. However, upon comprehending the symbolism, Allison showed great amusement and pleasure. As usual, after the show several professors got on the stage and sang limericks. Dr. Allison joined them, adding many new Scottish and English limericks. Several days after the show a letter arrived at the Club from Dr. Allison expressing his appreciation for having been included in the show and he enclosed a $100 bill for the recreation of the Pithotomists. He was consequently made an honorary member of the Club and presented with a Club tie. Soon afterward he returned to Oxford. In 1967 Dr. J. Donald Carmichael, who provided this anecdote, was at a dinner party in Alabama. Since it was a Wednesday evening, Dr. Carmichael was wearing his Pithotomy tie. An English woman at the party, after staring at the tie, finally said, "You know, that is very similar to my father's tie that we as children used to call his 'go to meeting tie'." The woman was Dr. Allison's daughter. Apparently he continued to wear his tie long after returning to Oxford from Hopkins.

John Adkins provides this followup on Dr. Allison:

I went to Duke for surgical training in 1965 and I religiously wore my Pithotomy tie every Wednesday. Sometime in the spring of 1966, Professor Allison was our visiting professor for a week. He gave a lecture to the surgical house staff and medical students one Wednesday. At the conclusion of the talk, during the Q. and A., he looked out into the audience and pointed at me and said, "Doctor, I would like to speak to you when we're finished." Of course, I, a lowly intern, was terrified. Maybe I had not paid sufficient attention. Had I dozed?

So, as the medical students left, I made my way down front. The house staff, curious about what was going on remained in their seats. Our chief, Dr. Sabiston, gave me a wary expression. Professor Allison stood beside him with a huge smile and I felt a bit of relief. "I saw you sitting up there. Should I call you brother?" It was then that I noticed that he and I were both wearing Pithotomy ties. We had a brief, very nice conversation, during which he told what a great time he had had when he was at Hopkins. He was particularly proud that he was an honorary Pithotomist.

If you look at Professor Allison's official photograph at Oxford University, you will note that he is wearing his Pithotomy tie: http://www.nds.ox.ac.uk/about-nds/history/professor-phillip-allison.

LEFT: Dr. Allison and Dr. Blalock enjoy the show.

This Britisher among us here

Has laughed with main and might

But as we warned you earlier

You won't get off tonight.

You've publicized the diaphragm

And are a famous cuss

But any friend of Al Blalock's

Is just a shit to us!

(photo and 3000 Years Ago Lyrics courtesy Ned Brockenbrough, '56)

The 1957 Pithotomy Show was memorable for a recent hernia repair done on Dr. Blalock by Dr. Rienhoff, commemorated in song as follows.

Don't know why

I can't button up my fly;

Got a hernia.

Keeps comin' out all the time.

Gettin' older day by day.

Phillip's gone away and left me.

There's no one here to help me.

And it certainly ain't a job for A. McGee.

But it hurts me on the tee, it hurts me when I pee,

Bill, won't you fix it for me?

THE 1960's AND EARLY 1970's

The decade of the 1960's was a period of transition for the Johns Hopkins Hospital and the Pithotomy Club. As the '60's began, most medical students and house officers lived in rowhouses surrounding the hospital, creating a true Hopkins community. The boarding houses for medical students were still largely in existence, continuing to provide an opportunity for medical students of different classes to interact so cially. The social life of the students was still centered around the Hospital area. During this decade, however, the boarding houses disappeared, the remaining fraternities died, and the neighborhood became increasingly dangerous. Students moved out to other parts of the city. Reed Hall, the student dormitory, became the chief source of housing for freshman students, but they usually moved away as soon as they could. Students who lived together usually lived with classmates, not members of other classes. The camaraderie cherished by those students from the 1950's who lived on Broadway or nearby streets found its last vestige in the Pithotomy club. The Club became the only place where students were able to become close friends with members of other classes and not just their own classmates. The Club dining room had become the only place for younger students to absorb the wisdom, advice, and encouragement from the upperclassmen. With such a dramatic change from the 1950's, the Club entered the 1970's.During the 1971-72 school year no one lived at the Clubhouse and there were about three dozen break-ins. The thieves took food, there being nothing else of value in the clubrooms. As a consequence, meals consisted of grilled cheese-bacon-tomato sandwiches because meat was regularly stolen. The next year Bill Thomson ('73) and Bill Nersesian ('73) moved into the Clubhouse, ending the break-ins. They visited the Washington Zoo one day and as always had security measures in mind. They noticed a big thick door that was being discarded from the elephant house, decided that it had great security potential, and somehow brought it back to Baltimore, where it was put on rollers, covered with steel signs (to provide extra protection from small caliber weapons), and placed on the third floor of the Club protecting the inhabitants from prowlers.

THE LATE 1970's TO THE END OF PITHOTOMY

By the late 1970's the Pithotomy Club continued to occupy a three story rowhouse at 731 N. Broadway. The basement was used for storage and contained the pool table donated by William Rienhoff. On the first floor was the dining room and kitchen. The dining room walls were covered with portraits of each Pithotomy class starting with 1897. Along the stairs and upstairs walls were numerous autographed photos of faculty going back to Osler. The second floor was a lounge, furnished with chairs and sofas, and a foosball table. On the third floor were sleeping rooms where two members lived. Every week a dinner guest from the faculty was invited to the Club. After dinner the guest gave a brief talk. These informal talks were not only educational, but they also gave the students a rare chance to see the faculty in a purely social and relaxed setting. The faculty members chosen were generally those who seemed most interested in the students and likewise relished the opportunity to talk informally with members of all four medical classes.The highlight of the year continued to be the Pithotomy Show, held the first week in May. The show was composed of a freshman-sophomore show which lampooned the basic science faculty, and a junior-senior show which lampooned the clinical faculty. The show was performed over four consecutive nights. Wednesday night's performance was a show for women, identical in every respect to the other performances. Thursday night was student night and Friday's performance was for house staff. The legendary beer throwing was a big part of the student and house staff nights and no one in the audience remained dry. On house staff night the assistant Chiefs of Service and Chief Residents sat on the front row and each was passed back during the show while being liberally doused with beer. Saturday night was reserved for faculty, and was more staid, with mint juleps replacing beer as the principal drink. On all nights the show began with a series of "Welcome Welcomes," obscene four-line verses written for each member of the audience. The tune is derived from the 1840 children's song "Reuben and Rachel." The first two Welcome Welcomes are traditional and go like this:

Welcome, welcome all you strangers.Likewise, the final two are also traditional:

Now it's time for this year's show.

Four long years we've ground our asses,

Now we let you bastards know.

In years gone by, don't ask me why

My predecessors have seen fit

As April wanes and May draws nigh

To ferret out each hypocrite

Often physiological functionsOn faculty night the show was followed by endless verses of "3000 Years Ago." The Welcome Welcomes and 3000 Years ago were sung by the president of the Club. For singing the Welcome Welcomes the president wore a graduation gown and mortarboard, and for the singing of "3000 Years Ago" he sat on a keg in the traditional manner, recapturing the spirit of the Max Broedel drawing.

Come to pass at times like this.

Please dear sirs do use the windows

When you need to pass your p___

With all the beer that you are drinking

There's no need to wait or dally.

Just remember when you go

The john this year is in the alley.

ABOVE: Some rare good publicity

for Pithotomy.

In 1980 the Club began a new activity, or more accurately, revived an old one, the Turtle Derby. The Turtle Derby was first held in 1931 at the Johns Hopkins Hospital when Colonel Frisby, the hospital doorman, kept a number of box turtles in what was called Frisby Farms. The idea occurred to race the turtles, and the Turtle Derby came into being. The house staff assumed sponsorship and the Derby became an increasingly extravagant affair and fund-raiser for Baltimore charities. Unfortunately, house staff apathy killed the Derby in 1977. In September of 1979, while dining at the Club, Dr. Henry Siedel, Associate Dean of Student Affairs, suggested that the Pithotomy Club revive the once-popular Derby. The Club undertook the project with much enthusiasm. The Pithotomy Club sponsored Turtle Derby, with the financial backing from the Hospital and School of Medicine, was held on May 16, 1980. Led by co-chairmen Gary Firestein ('80) and Charles Flexner ('82), the Derby was highly successful. Over one hundred turtles entered races and the Pithotomists sold over three hundred T-shirts and countless buttons. It provided entertainment for the hospital staff and many children from the Children's Medical and Surgical Center and raised money for good causes. The Turtle Derby, which is still going strong, can thus be added to the list of successful Pitotomy Club activities.

Unfortunately, several events came together in the 1980's leading to the death of the Club. Many observers think that the beginning of the Club's demise began with the 1982 show. The tradition of sparing women from Pithotomy humor had gradually eased as more women became faculty members. The 1982 show portrayed Dr. Bernadine Healy in a major role and it is safe to say the consequences were not good. She was highly offended by her portrayal in the show and demanded that the Club be punished and threatened a large lawsuit. The ensuing hard feelings took a toll and the criticism hurt the Club's reputation with some faculty and students. Although she soon left Hopkins, she continued to carping about the Club in several publications for years afterward. Soon after that controversy, the hospital bought the block the Clubhouse was on for another building project, forcing the club to move into far less ideal quarters on Madison Street. Meals could no longer be regularly offered so the club did not have the daily social interaction that made it so valuable. In spite of being the best known function of the Club to outsiders, the Show alone was not able to sustain sufficient student interest in the Club. Another factor at this time was the rapid increase in the number of women students, leaving far fewer potential members among the student body. In response to continued pressure and recognition of this fact, the Club eventually began accepting women members, although by that time the club's demise was inevitable. Yet another Hopkins building project encompassed the newest location and the Club building was donated to Johns Hopkins in 1992. After 95 years of existence, one of the outstanding traditions making Johns Hopkins unique became another chapter of Hopkins history. As for myself, I still cannot reproduce the taste of the Wednesday lunch cheese steak sub and I cannot hum a verse of "3000 Years Ago" without laughing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank the following physicians for so kindly writing or speaking to me about the history of the Club: William Rienhoff,III, Ernest Cross, Jr., Stewart Wolff, Charles Ellicott, Benjamin Baker, A. McGehee Harvey, Robert C. Kimberly, John Whitridge, Robert Mason, and Charles Flexner all of Baltimore, B. Noland Carter II of Richmond, Virginia, Ben Massey of Arcadia, California, Roger L. Greif of New York, Bill Nersesean of Freedom, Maine, R. Paul Higgins, Jr. of Cortland, New York, Strother Marshall of Barrington, Massachusetts, Hamilton W McKay Jr. of Charlotte, North Carolina, Eric W. Fonkalsrud of Los Angeles, Larry Miller of Great Neck, New York, J. Donald Carmichael of Birmingham, Alabama, Mason C. Andrews of Norfolk, Virginia, Julius Wilson of Santa Fe, C. C. Nuckols Jr. of Albany, New York, and John Sotos from somewhere in California. Dr. William H. Jarrett, II, of Atlanta has taken a special interest in the history of Pithotomy and been very supportive of this site, generously sharing his research into the Club's history. Special thanks goes to the late Dr. Alan C. Woods Jr. of Baltimore, not only for his help with this project but also for his years of selfless efforts on behalf of the Club.Home | About | History | 1897 Constitution | 1915 Constitution | 3000 Years Ago | Photographs